Documenting folklore

Documentation of Livonian folklore began with A. J. Sjögren’s research expedition to the Livonians in 1846. The traditions, beliefs, and proverbs he documented as well as those that were sent to him later by the Livonians were included in his Livonian grammar and language samples published in 1861. Finnish linguists continued to record Livonian folklore at then end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. In his expedition in 1888, E. N. Setälä recorded more than 80 stories, 140 proverbs, 110 riddles, a description of wedding traditions, and 20-30 songs. In his 1912 expedition with E. A. Saarimaa he made the first sound recordings of Livonian folklore using a parlograph.

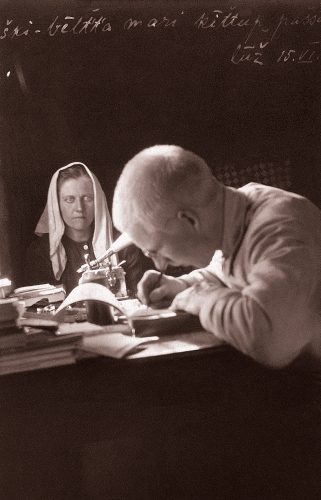

Oskar Loorits during the expedition. Lūžņa, 1920.

Estonian researcher Oskar Loorits (1900-1961) is responsible for the most noteworthy Livonian folklore documentation and research. His collection is currently located in the Estonian Literary Museum. One can also find the sound recordings of Livonian folklore made with O. Loorits’s assistance, which were made using a phonograph in the 1920s, but on records in the 1930s.

Thanks to his catalogue of Livonian story and legend types published in 1926, the Livonians are represented in international catalogues and studies of stories.

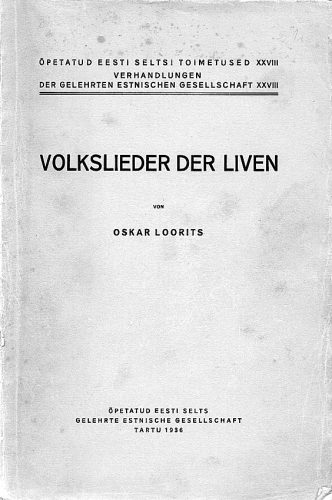

In 1936, O. Loorits published all the Livonian songs documented up to that point in his book Volkslieder der Liven. Most of these had been documented by Latvian musicologist and composer Emilis Melngailis. His most outstanding contribution to the study of Livonian folklore is his five-volume work “Livonian folk belief” (Liivi rahva usund) for which the young researcher received his doctoral degree in 1927. His study was published in Estonian and the final two volumes only appeared in print in 2000.

Livonian folksongs published by Oskar Loorits. “Volkslieder der Liven”, 1936.

Proverbs

Livonian proverbs have been carefully analysed. A scientific study of them and their correspondence to proverbs in Estonian and Latvian was published in 1981 in Estonia. Livonian Pētõr Damberg also participated in the creation of this work. 1088 unique proverb types are represented and these show that some proverbs stem from a Finnic source, while others are based on Latvian traditions.

Alā vaņtõl mīeztõ kibārõst ‘don’t see [judge] a man by his hat’ is the most popular Livonian proverb and has 17 variants. It is known among Latvians, Estonians, and Finns.

The second most popular proverb with 15 variants is Kārnaz karnõn silmõ äb knōb ‘a raven doesn’t peck the eyes of [another] raven’ is equally known in both the east and the west.

The third most popular proverb with 14 variants came from the Bible and is known across Europe Kis tuoizõn oukõ kōvab, se īž sizzõl sadāb ‘who digs a pit for another, falls into [it] themselves’.

Livonian storyteller Poulīn Kļaviņa. 1980ies.

Legends

Livonian legends have the same characters as those known from folk belief, which the Livonians called tijā usk ‘empty belief’, tūl usk ‘wind belief’, liekā usk ‘superfluous belief’, or mōņ usk ‘superstitious belief’. Though it has many beings, it is not organized using any kind of classification or hierarchy. Likewise, there are no detailed descriptions of the appearance of these beings or the course their lives. Beings in the Livonian supernatural realm included kōrajemā ‘herd mother’, mõtsāizā ‘forest father’, mõtsājemā ‘forest mother’, īeǟma ‘night mother’, lemǟma ‘warmth mother’, udjemā ‘fog mother’, mōŗadǟma ‘berry mother’, linādǟma ‘flax mother’, pȭzõjemā ‘bush mother’, sūojemā ‘swamp mother’, riekizā ‘road father’, and others.

Mierjemā ‘sea mother’ is most important of all. Mierizā ‘sea father’ and mierrovs ‘sea people’ lived with her.

The Sea Mother was the one who gave fishermen their catches and also granted them safe passage during storms. However, several other supernatural beings have roles related to this: tūljemā ‘wind mother’, tūlizā ‘wind father’, and touvõjemā ‘storm mother’. The Sea Mother is the only Livonian supernatural being who can be called a focus of genuine belief and associated rituals, which took the form of offerings. Offerings were made on significant dates, the first day at sea and also when there was a dangerous situation at sea. The most common offerings were food, spirits, string and yarn ends.

As a sailing people, the Livonians also believed in ship spirits or potõrmaņ. The Livonians believed that a potõrmaņ inhabited a ship for life at its construction. The departure of a ship spirit was a sign of impending disaster. These spirits were rarely seen, mostly they were heard banging, rattling, and even speaking in human language. This is how the spirits warned the crew of danger such as storms or damage to the ship. The Livonians also believed in other beings connected with water like sūraļ ‘the big grey one’ and naț ‘water maiden’. However, these are portrayed as negative spirits who are mostly interested in drowning people and especially children.

There are many legends and beliefs about the devil (kuŗē). His most important role was leading people astray (drinking, suicide, etc.). He also would capture souls and was a deceiver: it was believed that a person could get lost in a familiar place if they happened to find themselves on the devil’s path. Legends about wizards were very popular. The most common term for a wizard in recent centuries was buŗā, a borrowing from Latvian, but there were many other terms used besides this one. For example, kadsū or kadsīlma ‘jealous mouth, jealous eye, jealous one’. There is also a type of wizard referred to as a võl. This name was used for those who attended witches’ Sabbaths and drank milk from other people’s cows. At night a võl appeared as a shooting star, but during the day as “wizards’ spittle” (võlpaskā ‘wizard’s excrement’).

Livonians liked stories about hidden treasure and being brought to it in their dreams. The location of hidden treasure could also be known by “money fire” (rōtuļ), which was especially prevalent during holidays or on specific days of the week and was a sign that was taken very seriously by people.

There are many stories about the the kīlmakǟnga (Latvian: saltkurpis), which was the restless spirit of a person, especially a child, who had died prematurely or as a result of violence. These spirits often appear as a crowd of small children though they can also have an unspecified form. Fear of these sprits is mostly based on a general fear of those who died an unnatural death and especially of children who were born secretly to unmarried women and murdered (which means they were never baptized).

One of the Livonians’ favourite characters in their legends is the vīlkatõks ‘werewolf’. The Livonian name for werewolves comes from Latvian (vilkatis), but this may be because the original Livonian name was taboo. The most popular stories involve a man/werewolf who always manages to find fresh meat for his family, but to save time on his way to work turns into a wolf as he runs to the forest and home again later. There are legends about a priest who turns into a werewolf. The most well-known of these is about a werewolf with a white collar (the priest) who saves his maid from the other werewolves.